One to Watch

Electronic Arts Inc. (“EA”) has been out in the market with its tender offers and consent solicitations (“TOCS”) for more than a week. And it has successfully stirred up sentiment among bondholders who are considering their options against the currently still investment grade issuer. Given the potentially precedent setting nature of EA’s manoeuvre, it’s worth watching closely.

In the TOCS, Oak-Eagle AcquireCo, Inc. is offering to purchase EA’s US$ 750 million in 1.850% senior notes due 2031 (the “2031 Notes”) at a price of 91 cents on the dollar and its US$ 750 million in 2.950% senior notes due 2051 (the “2051 Notes”) at a price of 73 cents on the dollar if holders tender by February 24, 2026 and consent to certain amendments to the indentures (base indenture and second supplemental indenture).

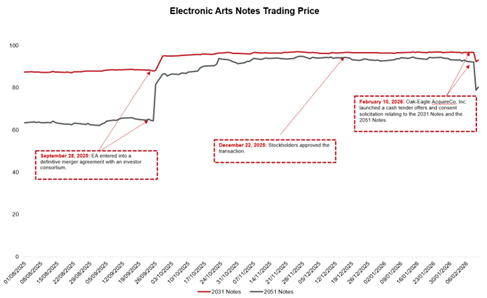

Sounds like a steep discount? Well, note that the 2031 Notes traded in the 80-cents range and the 2051 Notes in the 60-cents range for most of 2025, with their trading prices significantly increasing in late September when an investor consortium, including Silver Lake Management, Affinity Partners and Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, announced to take EA private. The take-private, once consummated and if triggering a downgrade of the notes from investment grade to junk bond status, would constitute a Change of Control Repurchase Event under the indentures, entitling bondholders to a payment equal to 101% of the aggregate principal amount of the bonds plus any accrued and unpaid interest to the repurchase date (the “CoC Payment”).

To put it differently, the bonds traded up because holders expected to receive the CoC Payment. As investment grade bonds, EA bonds are held by traditional asset managers and insurance companies, but likely quite a few opportunistic buyers, i.e., hedge funds, bought into the bonds in September expecting to make a windfall by buying at prices in the low sixties and eighties, respectively, and receiving the CoC Payment not too much later! The completion of the take-private is planned for the second quarter of 2026. So far, neither S&P nor Moody’s has downgraded the bonds, but both agencies have placed them on their watchlists, and observers think the downgrade is likely given the additional leverage stemming from the take-private.

The TOCS change everything because the proposed indenture amendments would open a path for EA to avoid the CoC Payment and likely expose opportunistic buyers to tax risks. That is unheard of and may deter opportunistic buyers from trading into similar situations in the future. It is also a smart way of leveraging changes in the interest rate environment over recent years and has been chatter among creative investment bankers at least since early 2023. Before you get out your popcorn, let’s consider how the spectacle may unfold.

Assuming the majority of the holders refuse to consent to the proposed indenture changes, EA is left with either making the CoC Payment or repaying the bonds at the Make-Whole Price in an optional redemption. Note that a few holders will have accepted the tender in any case and that any reduction in principal would be a win for EA as refinancing the bonds would enormously increase EA’s debt load. Here is what one commentator has to say about the interest expense:

“The 2031s and 2051s were issued at incredibly cheap rates during the 2021 zero-rate era, carrying a blended 2.4% coupon across $1.5 billion of paper. If the sponsors refinance this $1.5 billion at a hypothetical cost of 7%, the annual interest expense jumps from $36 million to $105 million. That’s a $69 million delta. Relative to $2.4 billion of EBITDA, you could argue this doesn’t matter much. But PV that $69 million annual cost over a five-year hold period and you’re looking at roughly $275 million. If you could avoid paying that, why wouldn’t you?”

For EA, the CoC Payment is very expensive. Of course, EA is said to be working with rating agencies to maintain the investment grade rating given the costly implications of a downgrade for the debt pile used to finance the take-private, but it is unclear how realistic that is.

EA’s alternative, cleaning the balance sheet through an optional redemption at par is slightly less expensive. Given today’s rate environment, the make-whole payment–the greater of (i) par value and (ii) the sum of the present value of the remaining scheduled interest and principal payments, discounted at T+12.5 bps for the 2031 Notes and or T+15 bps for the 2051 Notes–amounts to a payment at par, given that the discounted payments come out below par.

Now let’s assume the majority of the holders of the 2031 Notes and the 2051 Notes consent and the proposed amendments are implemented. EA and its new sponsors would have several reasons to be happy. First, EA would have reduced the principal of both the 2031 Notes and the 2051 Notes, by at least by $375 million, in each case. Second, with the amended indentures, EA would be able to use the legal defeasance clause to retire the bonds at a significantly less than the CoC Payment or the Make-Whole Payment.

The legal defeasance mechanism would permit EA to legally satisfy and extinguish the indenture and the notes on the 91st day after placing sufficient, high-quality assets into an irrevocable trust covering all remaining principal and interest payments under the bonds. That sounds like a lot of money or US treasuries, but again, consider today’s rate environment. As one observer notes:

“At today’s long Treasury rates of about 4.7%, funding a 2.95% coupon bond requires depositing significantly less than par. The present value math works out to roughly 74 cents on the dollar.”

Now, usually, the legal defeasance mechanism would include provisions protecting holders, most importantly a requirement to deliver a ruling from the IRS assuring that holders would not recognize income, gain or loss for federal income tax purposes as a result of the legal defeasance and would be subject to federal income tax on the same amount, in the same manner and at the same times as would have been the case without the defeasance. These protections are being removed in the proposed amendments.

With the tax protections removed, holders would run the risk that the deposit would constitute a significant modification of the bonds, which pursuant to IRS regulations would constitute a “deemed exchange,” resulting in a taxable event. Specifically, opportunistic holders who bought into the bonds when they were trading low could be forced to recognize a taxable gain without ever having received cash. That’s a trade backfiring big time: Expecting the CoC Payment in cash and instead being subject to taxes without any cash receipt. The tax treatment will vary from holder to holder, depending primarily on purchase price and tax jurisdiction, which will likely make it difficult for bondholders to get organized as a group.

As part of the proposed amendments, EA is also stripping out the tax treatment protections from the covenant defeasance mechanism. It is doubtful whether the covenant defeasance mechanism could actually help EA in cleaning its balance sheet. Unlike legal defeasance, where the Issuer is released from the debt entirely, the covenant defeasance mechanism only releases the Issuer from the restrictive covenants. Arguably, the Change of Control Repurchase Event provisions cannot be defeased as part of the covenant defeasance as they are not covenants but repurchase rights.

Where does all of this leave the bondholders? Well, to say the least, receiving the CoC Payment has become a long shot. But it may be worth fighting for more than 74 cents on the dollar (in case of the 2051 Notes) and forcing EA to the table. In a potential litigation, the holders’ main argument ought to be that the amendments to the legal defeasance mechanism are effectively amendments to the right to repurchase the bonds and therefore require the consent of all holders rather than just a majority. However, if EA manages to time the downgrade to occur only after the 91st day after the deposit, as a result triggering the CoC Payment only after the indentures have already been defeased, this argument may not catch. Similarly, arguments based on a potential impairment of the right to full repayment may not work as the bondholders will receive full repayment from the defeasance trust. A more promising argument may be the securities law treatment of the deposit. For tax purposes, the obligation of the trust is a “new bond.” Should the obligation also be a “new bond” for securities law purposes, which would require registration or exemption from the registration requirement under the U.S. Securities Act of 1933? Potentially, holders could craft a securities law violation argument bringing in a regulatory angle.

There is a potential for the whole scene to get ugly and EA is certainly rattling with its sabre, but it is far from certain that they will indeed use the legal defeasance mechanism. If anyone accepts the tender, EA is already winning given the reduction in principal. So, they may refrain from driving a hard bargain and be willing to avoid lengthy litigation. After all, making a reputation as a particularly aggressive debtor and being in a major fight with parts of the market while syndicating large junks of (take-private) debt may not go well.

Thinking large picture: The spectacle speaks to the tone in the market. The unthinkable is possible today and there are no taboos. Concrete implications for future contracting practices in the bond market may be holders insisting on the deletion of the legal defeasance mechanism from bond indentures altogether or requiring its inclusion in the catalogue of sacred rights, which requires all-holder consent for amendments.

Maria C. Schweinberger